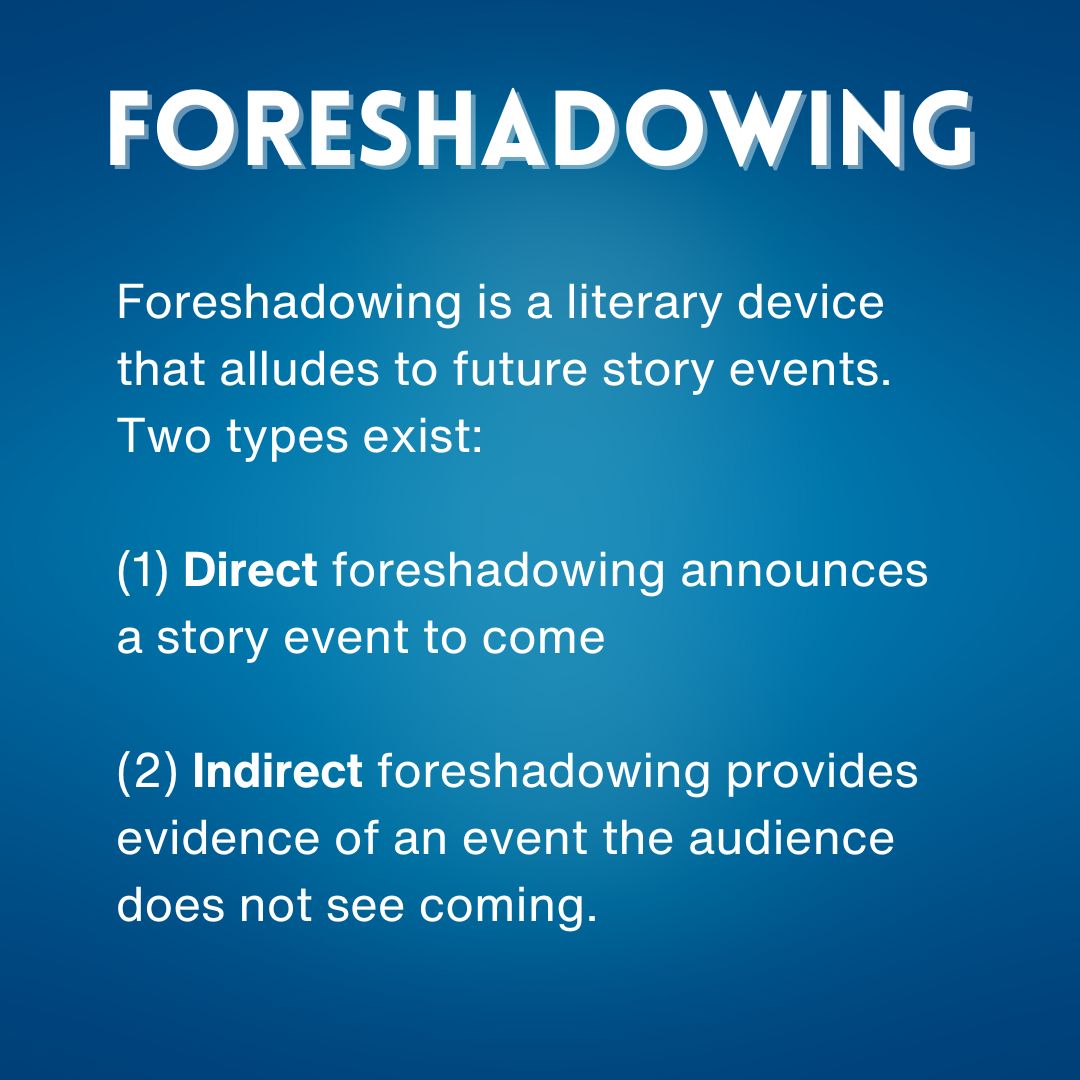

Foreshadowing - Write a Captivating Story [Definition, Examples, Tips]If you're writing a book, screenplay, or short story, you want to keep your audience glued to your story and deliver satisfying surprises. Foreshadowing is a tool that can help. In this post, I give you the definition of foreshadowing, examples of foreshadowing, and tips for applying this powerful literary device to your story. Want to write an awesome story? Download my FREE outlining guide. Foreshadowing definitionForeshadowing is a literary device that alludes to future story events. Two types exist: (1) Direct foreshadowing announces a story event to come (2) Indirect foreshadowing provides evidence of an event the audience does not see coming. Direct foreshadowingBelow are examples and tips for direct foreshadowing... 5 examples of direct foreshadowingIn these examples, major plot event to come are foreshadowed in a clear way to the audience:

Tips for direct foreshadowingCreate Suspense Direct foreshadowing is a great way to build anticipation. Once you announce an event is going to occur in your story, your audience will start thinking about the implications of that event, most notably, how it will affect the lives of characters. If you've done a good job creating a connection between your audience and characters, your readers will be emotionally invested in the impact these story events have on characters. A feeling of suspense is created while the audience waits to see how the events will shape the lives of the characters. Keep the Stakes High The higher the stakes of an event, the more emotionally invested the reader will become in the outcome, and the stronger the feeling of suspense. For instance, in the example with Hank, a hurricane is a high-stakes event. A hurricane can devastate homes, even end lives. If the reader has a connection with Hank - and others in the town - the reader will start worrying about the hurricane the moment it's mentioned. If, on the other hand, Hank heard about a mild rain that was nearing, the drama would be flat. In the example with Jenny, if the audience has a connection with her, and knows her dream, readers will eagerly await the outcome of a singing competition that has the potential to make her dream a reality. If, on the other hand, Jenny heard about a talent show at a local rec center, yes, the audience may root for her to win, however, the stakes - and drama - would not be nearly as high as her competing in a national contest on TV. Make Them Wait Once you've established a high-stakes story event is coming, the next tip is to wait a while before you take the reader to the event. The wait sustains the feeling of suspense. That's where the "edge of your seat" effect comes from. After Hank hears about the hurricane, before it strikes, you might show him analyzing an in-depth weather report online. You can even have him convinced the warning is a false alarm, and he avoids taking precautions like boarding up his windows. The audience's worry will grow as it waits to see how bad the storm will be. Though people don't like worrying about things in real life, they do in stories. Keep them in this worried state for as long as doable. After Jenny hears about the singing competition, you might show her practicing. Possibly she practices so much, her sleeping suffers. As the contest approaches, she gets sick and loses her voice. The audience's worry will be heightened. Keep the audience worrying until the end of the competition. Be Sure to Deliver Direct foreshadowing is a sort of promise you make to your reader. You're suggesting that a very interesting plot event will happen. If you make the suggestion, and then do not eventually put the event in your story, your audience will feel ripped off. This does not mean the event needs to play out exactly as it's initially suggested. This simply means the event needs to show up in the story in some form. For example, in a horror story, Leah receives a note from the villain saying "I'm going to kill you." This does not mean the villain has to eventually kill her. However, the audience will be expecting the villain to at least try. Even if Leah gets away unscathed, the killer should attack her at some point in a dramatic scene. Indirect foreshadowingBelow are examples and tips for indirect foreshadowing... 5 examples of indirect foreshadowingIn these examples, major plot event to come are foreshadowed, yet the audience would not be able to necessarily anticipate them:

Tips for indirect foreshadowingPlant and Payoff Planting and payoff is a writing technique that involves "planting" story elements in the minds of your audience that eventually go on to have a "payoff." In the example with Gary, the saxophone story element was planted in the minds of readers. The payoff from this element comes when he hits the criminal during a dramatic break-in scene. As a general rule, if a major plot event features a certain story element, you should show that story element to the audience considerably earlier, even if briefly. These story elements may be physical objects, like a saxophone, however, can be any variety of things (ex, maybe a song or a dream). Showing the audience the element establishes it as part of the story's world. When the element is later used in a dramatic plot event, that scene would feel more authentic than it would if the element first popped up during the dramatic moment. For instance, if Gary was being attacked by the villain, and grabbed a big metal instrument the audience never saw before, the scene would feel inauthentic. The saxophone would seem like a too convenient, unrealistic fix to Gary's problem, versus an organic extension of his world. Create Awesome Twists Audiences love twists. However, if you don't follow certain steps, your twists may be guessable or non-believable. An effective twist needs to strike a fine balance. For believability, you need to give the audience clues about the information eventually revealed in the twist. However, if these clues are too obvious, your audience will be able to guess the twist before it happens, wiping out the crucial shock factor. In the example with Sally, the twist in her story is that she is a murderer. To make that twist shocking, Sally should not come off like a murderer beforehand. For instance, maybe she's a friendly mother of three who volunteers at a hospital. Sally arriving home with dirty shoes is a clue that she was burying a body in the woods. However, it's not an obvious clue, whereas her showing up with blood on her shoes would be. Sally is able to dismiss any suspicion by saying she stepped in a puddle. However, before she gives the answer, she should hesitate. Only for a second, but long enough to hint at a potential lie. After the audience finds out she is the murderer, the conversation about the shoes will add credence to the revelation. On the other hand, if Sally is shown to be a pleasant woman through the story, then is revealed as a killer without any clues the audience can reference, the twist will feel inorganic. The audience may be surprised, yet not satisfied. Readers prefer when evidence of a twist is shown to them, yet in subtle ways they can't understand until after the reveal. What genres use foreshadowing?The foreshadowing storytelling technique - both the direct and indirect varieties - can be used in any genre of fiction or narrative non-fiction, such as:

Want more writing tips?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed