Use These 10 Literary Devices to Tell an Awesome StoryIf you're writing a book, screenplay, or short story, you want to captivate your audience with your characters and settings, build suspense, and deliver strong emotional payoffs. Literary devices are tools that can help. Though plenty of literary devices exist, these 10 are particularly useful in fiction and narrative non-fiction. Check out these examples and tips for using them to tell an awesome story. Want to write an awesome story? Download my FREE outlining guide. What is a literary device?A literary device is a technique writers can use to make stories more engaging. These tactics can create suspense, evoke emotion, set up a plot twist, and more. Alliteration, symbolism, and foreshadowing are examples of literary devices. 10 literary devices for your storyBelow are definitions of 10 powerful literary devices for your book, screenplay, or short story. Click the "Learn More" links to see examples of each literary device and tips for applying it to your story. #1 - SymbolismSymbolism is when an element of your story - like a character, setting, or object - represents an idea. The represented idea tends to play a significant role in the story's character development, plot, or theme. For instance, in a prison story, grass might be a symbol for freedom. Learn More #2 - ToneTone is the attitude a writer takes toward the events in a story. Though characters may have distinct attitudes, the literary device tone just refers to the attitude of the writer. Some examples of tone are optimistic, comedic, and regretful. Learn More #3 - MoodMood is the overall feeling of a scene. Chaotic, warm, and sad are examples of moods. One story can have many moods, since different scenes can create different emotional responses from an audience. Learn More #4 - ImageryImagery is a literary device writers use to connect with any of the audience's five senses: sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. Imagery is often used in the descriptions of characters, settings, and plot events. Learn More #5 - MetaphorA metaphor falsely asserts that one thing is another while creating a true, symbolic comparison. "The office is an igloo" is an example of a metaphor. Learn More #6 - PersonificationPersonification is the granting of human qualities to non-human elements in a story, like vehicles, houses, and even concepts, such as hope or doubt. Learn More #7 - ForeshadowingForeshadowing is a literary device writers use to allude to future events in a story. Two kinds exist: (1) Direct foreshadowing states a story event is to come (2) Indirect foreshadowing gives evidence of an event the audience does not anticipate. Learn More #8 - Dramatic ironyDramatic irony is a literary device in which a writer gives information to the audience that a character, or multiple characters, is unaware of. The tactic can build suspense. Learn More #9 - MotifA motif is a repeating element in a story that plays a strong role in the story's theme. Motifs can be abstract ideas, like triumph or deceit. They can also be parts of your story's physical world, such as buildings, objects, colors, and noises. Learn More #10 - AlliterationAlliteration is the repetition of a consonant sound at the start of two or more close-together words, as in "warm weather," with "w" the repeating sound. Learn More Why use literary devices?Here are just some storytelling components literary devices can help you with:

What genres use literary devices?Literary devices are used across fiction and narrative non-fiction. Some examples of genres that use literary devices:

How to use literary devicesLiterary devices should serve the story you're telling. Once you have an idea of your characters and your plot, and you begin writing your first draft, you'll need to accomplish various tasks to make any scene work. For instance, let's say your main character in a thriller is running from three gunmen in a scene. For this scene to work, a task of yours could be making the audience fear for your protagonist's life. A combination of literary devices can be applied to accomplish that task. You can use dramatic irony to make your protagonist unaware of the danger lurking around the corner. Once the protagonist sees the gunmen, you can leverage mood to create a feeling of desperation. You can also apply imagery to show the physical effects of panic, like sweat and an accelerating heartbeat. Think of literary devices like specialized tools. Let your story tasks dictate when and how you apply these tools. What to avoid when using literary devicesAs stated, the writing tasks you need to accomplish to make a scene work should determine what literary devices you use - avoid the opposite approach, ie, deciding you want to use a certain literary device and then bending the purpose of a scene just so the device can fit. You also want to avoid literary devices drawing attention to themselves. They should help your scenes flow, not cause the audience to focus on the device. Certain devices, like alliteration, can draw attention to themselves if used too often. Other devices, like tone, can draw attention to themselves if shifted through a story. Once you gain a deeper understanding of the 10 literary devices outlined above (with the "Learn More" links), you should have a good idea of how to apply them to your story in a natural way.

0 Comments

Creating an Immersive Mood in Your Story: Examples and TipsIf you're writing a book, screenplay, or short story, you want to create an immersive experience for your reader. You want to pull the audience into your scenes and deliver strong emotional payoffs. Mood is a powerful literary device than can help you do that. In this article, I tell you what a mood in storytelling is, provide examples, and offer tips. Want to write an awesome story? Download my FREE outlining guide. What is mood in writing?Mood in writing is the overall feeling of a scene. Exciting, lighthearted, and somber are examples of moods. A story can have multiple moods, as different scenes can evoke different emotional responses from the audience. The importance of mood in storytellingThe four key elements of a story are character, plot, theme, and emotional impact. Since mood is based on feeling, it's a great tool for enhancing the emotional impact of your story. Each scene should have a distinct mood that's tied into its central conflict. Is your main character running from a serial killer? Fear would be a natural mood for that scene. If you can play up the feeling of fear, you can evoke a strong emotional reaction from your audience. Pulses will go up as they turn the pages. On the other hand, if the mood you're creating doesn't fit with the central conflict of your scene, you can ruin what might be an otherwise great scene. For example, let's say you're writing a scene where the main character just finds out his sister is missing. A mood of anxiety would be a natural fit. However, if you instead gave the scene a detached feel, where the main character doesn't care much, the audience wouldn't care much either. It would feel flat. How mood relates to tone and genre in writingTone is another literary tactic. It refers to the attitude a writer takes toward the events in a story. Unlike mood, which can show up in a different form in various scenes, a story should have just one tone. Examples of tone would be sarcastic, serious, or nostalgic. The tone you choose for your story narrows the moods you can pull off in it. For example, if your story has a sarcastic tone, a somber scene may be difficult to make workable. If, instead, your story had a serious tone, a somber scene would be a natural fit. The genre you write in shouldn't necessarily limit the mood of any scene, however, in totality, the moods of your scenes should align with audience expectations for your genre. For example, if you're writing a horror story, you absolutely can have a scene with a funny mood. Possibly, toward the beginning of the story, before the killer is loose, you can characterize your protagonist by showing her joking around with her friends. However, if your story goes to have 50 scenes total, and 40 of them wind up having a funny mood, your story won't feel like a horror one. Horror readers expect moods like fear, worry, and excitement in the majority of their scenes. Thus, be mindful of mood expectations in your genre. Feel free to go in different directions, but only in small doses. How to create a mood in storytellingThe characters in your scene are the conduits for creating a mood for your audience. What the characters feel directly impacts what your audience feels. Thus, to create a mood, you want to capture the emotional state of your characters. Here are three tips: #1 Create mood with dialogueDialogue is what your characters say to each other. How the characters feel should be reflected in how they talk (even if they're lying, ie subtext). For instance, let's say one character in a scene is training another for a boxing match. While the trainer yells at the boxer, the dialogue would create a mood of intensity. Or maybe you have a scene where one character is warning others about a terrible storm blowing into town. As the characters worry about the storm, an overall mood of worry will emerge. #2 Create mood with settingWith an effective setting, you can create a mood without your characters even speaking. Let's say you're writing a sci-fi story. Your protagonist, who's from Earth, winds up traveling to a different planet. This planet is technologically about 10,000 years ahead of Earth. When your character first arrives and marvels at all the high-tech infrastructure, a mood of awe will be produced. Your character doesn't need to say she's in awe. The setting alone will get the point across. #3 Create mood with plot eventsPlot events should unfold in a cause-and-effect way, with scenes building off one another. Thus, if your main character appears in scene C, the audience may already have a good idea of what's at stake because of previous scenes A and B. For instance, let's say your protagonist, from Nebraska, has been practicing for a singing competition in Los Angeles. If a scene opens with a plane landing in Los Angeles, a feeling of anticipation would be created. Based on past events, the audience knows the high stakes of the LA trip. Though scenes should follow a cause-and-effect flow, they absolutely can be filled with surprises. A surprise is an abrupt plot event that characters did not see coming. Surprise has the ability to create a strong mood in an instant. For instance, let's say you're writing a scene where two couples are enjoying a beach vacation. The scene has a lighthearted mood. Then, a woman discovers a dead body behind a bush. The mood of the next scene immediately becomes panic. The simple reveal of a dead body is all that was needed to produce this strong mood. Build on the mood you createIf you're able to create a distinct mood for a scene, you're off to a good start. Next, you want to build on this mood, ratcheting up its emotional force. Let's go back to the example of a character running from a serial killer. We've established a mood of fear. How can we escalate the feeling of fear? Here's a possible sequence of events that could accomplish this:

What genres use mood?Mood is used across fiction and narrative non-fiction. Some examples of genres that use mood:

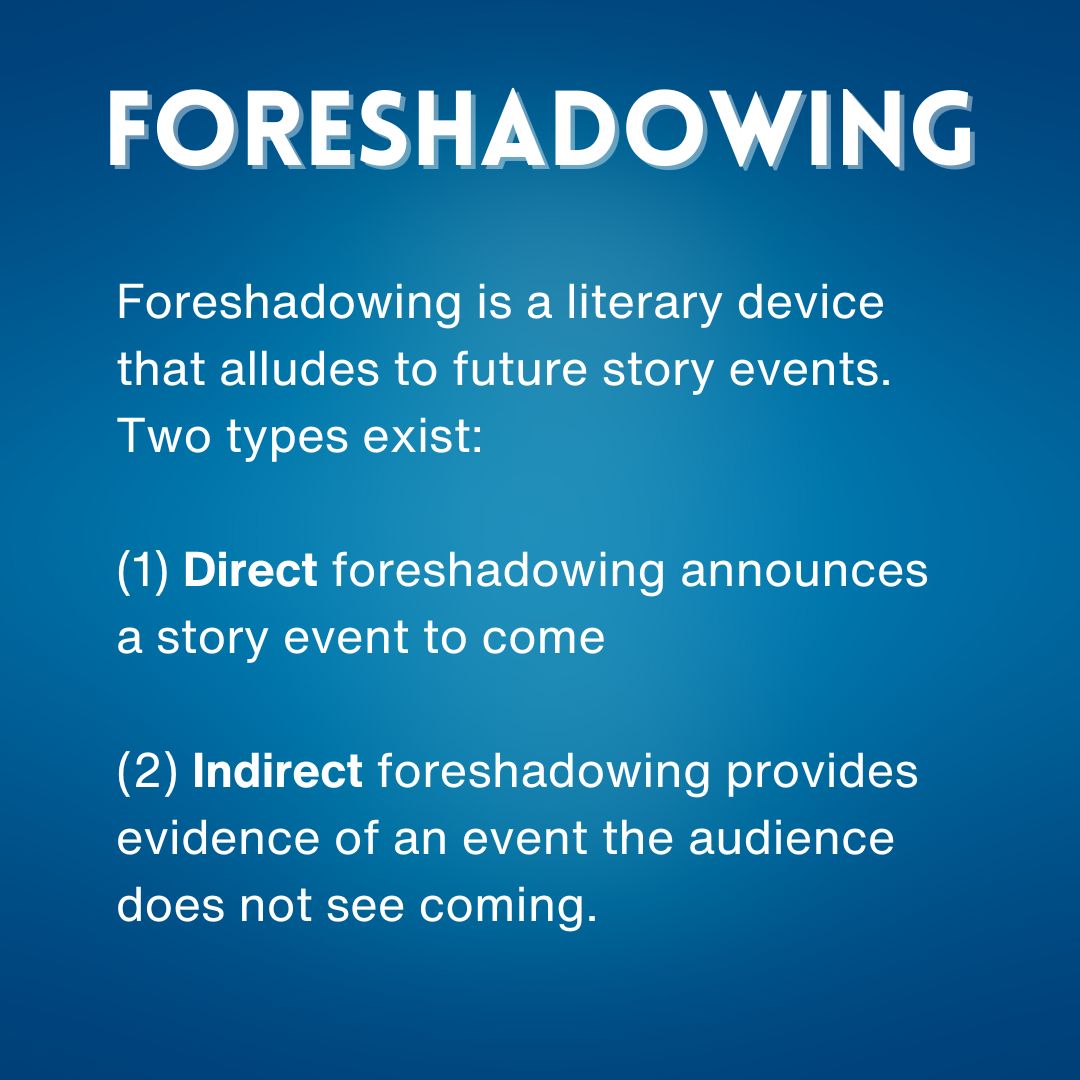

Want even more writing tips?Foreshadowing - Write a Captivating Story [Definition, Examples, Tips]If you're writing a book, screenplay, or short story, you want to keep your audience glued to your story and deliver satisfying surprises. Foreshadowing is a tool that can help. In this post, I give you the definition of foreshadowing, examples of foreshadowing, and tips for applying this powerful literary device to your story. Want to write an awesome story? Download my FREE outlining guide. Foreshadowing definitionForeshadowing is a literary device that alludes to future story events. Two types exist: (1) Direct foreshadowing announces a story event to come (2) Indirect foreshadowing provides evidence of an event the audience does not see coming. Direct foreshadowingBelow are examples and tips for direct foreshadowing... 5 examples of direct foreshadowingIn these examples, major plot event to come are foreshadowed in a clear way to the audience:

Tips for direct foreshadowingCreate Suspense Direct foreshadowing is a great way to build anticipation. Once you announce an event is going to occur in your story, your audience will start thinking about the implications of that event, most notably, how it will affect the lives of characters. If you've done a good job creating a connection between your audience and characters, your readers will be emotionally invested in the impact these story events have on characters. A feeling of suspense is created while the audience waits to see how the events will shape the lives of the characters. Keep the Stakes High The higher the stakes of an event, the more emotionally invested the reader will become in the outcome, and the stronger the feeling of suspense. For instance, in the example with Hank, a hurricane is a high-stakes event. A hurricane can devastate homes, even end lives. If the reader has a connection with Hank - and others in the town - the reader will start worrying about the hurricane the moment it's mentioned. If, on the other hand, Hank heard about a mild rain that was nearing, the drama would be flat. In the example with Jenny, if the audience has a connection with her, and knows her dream, readers will eagerly await the outcome of a singing competition that has the potential to make her dream a reality. If, on the other hand, Jenny heard about a talent show at a local rec center, yes, the audience may root for her to win, however, the stakes - and drama - would not be nearly as high as her competing in a national contest on TV. Make Them Wait Once you've established a high-stakes story event is coming, the next tip is to wait a while before you take the reader to the event. The wait sustains the feeling of suspense. That's where the "edge of your seat" effect comes from. After Hank hears about the hurricane, before it strikes, you might show him analyzing an in-depth weather report online. You can even have him convinced the warning is a false alarm, and he avoids taking precautions like boarding up his windows. The audience's worry will grow as it waits to see how bad the storm will be. Though people don't like worrying about things in real life, they do in stories. Keep them in this worried state for as long as doable. After Jenny hears about the singing competition, you might show her practicing. Possibly she practices so much, her sleeping suffers. As the contest approaches, she gets sick and loses her voice. The audience's worry will be heightened. Keep the audience worrying until the end of the competition. Be Sure to Deliver Direct foreshadowing is a sort of promise you make to your reader. You're suggesting that a very interesting plot event will happen. If you make the suggestion, and then do not eventually put the event in your story, your audience will feel ripped off. This does not mean the event needs to play out exactly as it's initially suggested. This simply means the event needs to show up in the story in some form. For example, in a horror story, Leah receives a note from the villain saying "I'm going to kill you." This does not mean the villain has to eventually kill her. However, the audience will be expecting the villain to at least try. Even if Leah gets away unscathed, the killer should attack her at some point in a dramatic scene. Indirect foreshadowingBelow are examples and tips for indirect foreshadowing... 5 examples of indirect foreshadowingIn these examples, major plot event to come are foreshadowed, yet the audience would not be able to necessarily anticipate them:

Tips for indirect foreshadowingPlant and Payoff Planting and payoff is a writing technique that involves "planting" story elements in the minds of your audience that eventually go on to have a "payoff." In the example with Gary, the saxophone story element was planted in the minds of readers. The payoff from this element comes when he hits the criminal during a dramatic break-in scene. As a general rule, if a major plot event features a certain story element, you should show that story element to the audience considerably earlier, even if briefly. These story elements may be physical objects, like a saxophone, however, can be any variety of things (ex, maybe a song or a dream). Showing the audience the element establishes it as part of the story's world. When the element is later used in a dramatic plot event, that scene would feel more authentic than it would if the element first popped up during the dramatic moment. For instance, if Gary was being attacked by the villain, and grabbed a big metal instrument the audience never saw before, the scene would feel inauthentic. The saxophone would seem like a too convenient, unrealistic fix to Gary's problem, versus an organic extension of his world. Create Awesome Twists Audiences love twists. However, if you don't follow certain steps, your twists may be guessable or non-believable. An effective twist needs to strike a fine balance. For believability, you need to give the audience clues about the information eventually revealed in the twist. However, if these clues are too obvious, your audience will be able to guess the twist before it happens, wiping out the crucial shock factor. In the example with Sally, the twist in her story is that she is a murderer. To make that twist shocking, Sally should not come off like a murderer beforehand. For instance, maybe she's a friendly mother of three who volunteers at a hospital. Sally arriving home with dirty shoes is a clue that she was burying a body in the woods. However, it's not an obvious clue, whereas her showing up with blood on her shoes would be. Sally is able to dismiss any suspicion by saying she stepped in a puddle. However, before she gives the answer, she should hesitate. Only for a second, but long enough to hint at a potential lie. After the audience finds out she is the murderer, the conversation about the shoes will add credence to the revelation. On the other hand, if Sally is shown to be a pleasant woman through the story, then is revealed as a killer without any clues the audience can reference, the twist will feel inorganic. The audience may be surprised, yet not satisfied. Readers prefer when evidence of a twist is shown to them, yet in subtle ways they can't understand until after the reveal. What genres use foreshadowing?The foreshadowing storytelling technique - both the direct and indirect varieties - can be used in any genre of fiction or narrative non-fiction, such as:

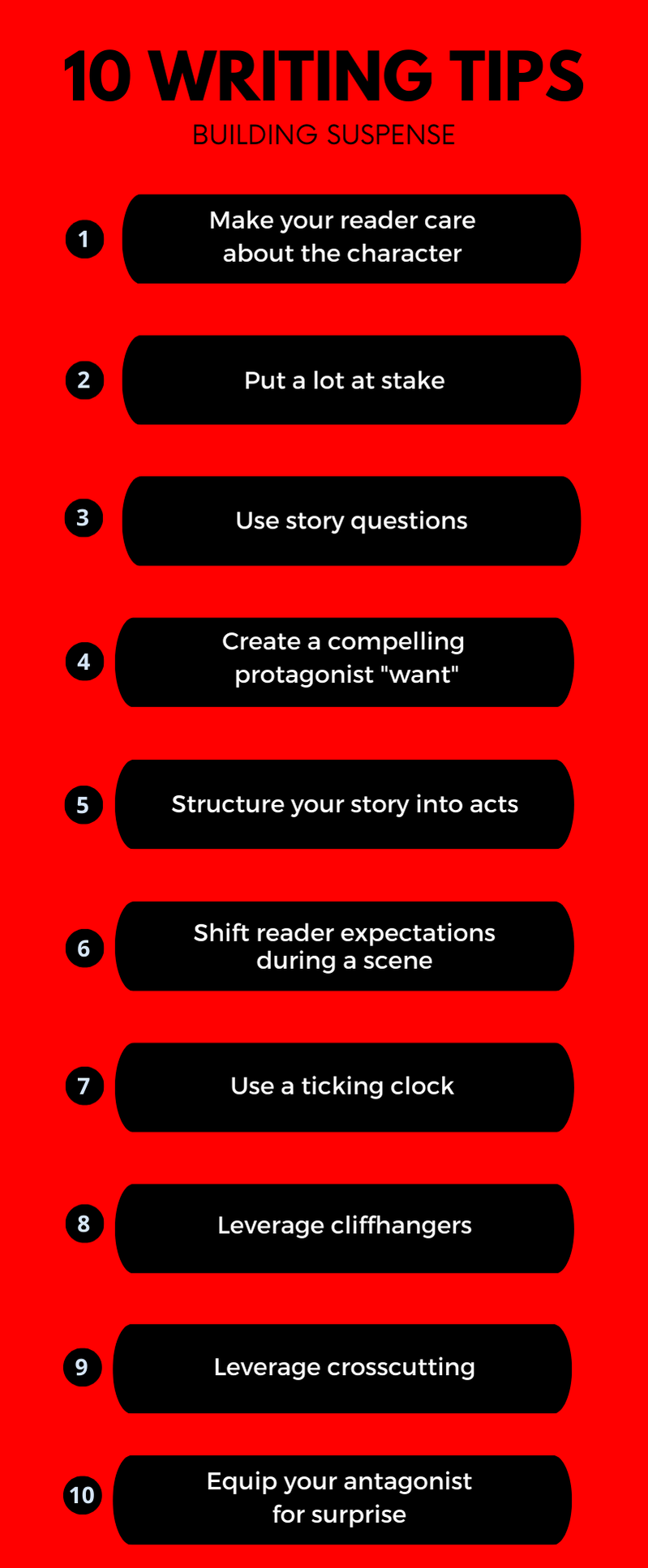

Want more writing tips?10 Can't-Miss Tips for Writing a Suspenseful Book or ScriptWant to create a page-turning story? Check out these 10 tips for writing a suspenseful book, or script, that will keep readers excitedly flipping your pages. Want to write an awesome story? Download my FREE outlining guide. Suspense Tip 1 - Make your reader care about the characterSuspense is heightened the more the reader wants to know a piece of information. A reader's desire for a certain piece of information increases the more the reader cares about the character involved. For example, if a reader feels a deep connection to your protagonist, and that character is on trial for a murder he didn't commit, the reader will feel a lot of suspense awaiting the verdict. On the other hand, if a minor character that the reader never got a chance to know was on trial for murder, the reader wouldn't care much about the verdict, ie not much suspense. Since your protagonist drives the plot of your story, and most suspense will be around that character's outcomes, I suggest you learn how to create a protagonist the reader cares about. That being said, supporting characters can absolutely be the subjects of suspense scenes too. Make sure you've at least developed some empathy between the reader and character if you want these scenes to work well. Suspense Tip 2 - Put a lot at stakeLet's stay your reader cares a lot about a character and you decide to create a suspense scene around that character. You're off to a good start. You raise a question the reader wants the answer to. However, for some reason, when you read the chapter's draft, you're not on the edge of your seat. What happened? Likely, not much is at stake. For instance, if your reader cares a lot about a character named Michelle, who's stuck in traffic on the way to work, the audience may wonder, Will she make it to the office on time? However, this question isn't that suspenseful without something major at stake. If Michelle happens to show up 15 minutes late, nothing terrible will happen to her. She doesn't have much to lose. Instead, if Michelle has a potentially career-changing presentation with her company's biggest client, now something is at stake. The busy client only has 30 minutes at the office before having to leave for another appointment. If Michelle is late, she won't have enough time for her presentation. And if the presentation doesn't go well, she'll lose out on the promotion to her dream job. Suspense Tip 3 - Use story questionsA story question is a certain type of question the reader wants the answer to. However, unlike other suspense questions, it's rarely answered in the chapter where it was raised, but much later in the story. As mentioned, suspense is elevated the longer the reader must wait for a question's answer. Thus, story questions, with their long time horizons, lend themselves to effective suspense. Here's an example of how story questions can play out...

The reader will have to keep turning the pages for the answers to those four story questions. Suspense Tip 4 - Create a compelling protagonist "want"Your protagonist's "want" is the main goal they're after through the story. For instance, in a detective novel, the want may be catching a serial killer. Whether or not your protagonist attains the want shouldn't be revealed until the climax of the story, just before the end. This time delay makes for good suspense. However, you also need to make sure a lot is at stake for your protagonist. As mentioned, when characters have a lot to lose if a story outcome turns out negative, readers become more emotionally invested in the result. In the detective example, if the killer isn't caught, he's almost definitely going to carry out five more murders he's planned. Innocent people will die and the detective will be forced to shoulder the guilt, ie a lot to lose. To learn more about creating a great protagonist want, check out my post on story plot tips. Suspense Tip 5 - Structure your story into actsAs discussed, your protagonist should have an overarching want that propels the events of the story until the end. To turn up the suspense along the way, you should structure your story into acts. The beginning and middle acts would build to answer their own questions, which would serve as sub-questions to whether or not the main character achieves the main goal. For example, if a detective's main goal is catching a serial killer, the reader would receive a definitive answer in the final act. However, in the two previous acts, the events in the story would build to answer two important related questions:

Since these questions are related to the story's main one, if you did a good job crafting the main one, the earlier act questions will immediately become important to the reader. To learn more about acts, check out my post on structuring your story into acts. Suspense Tip 6 - Shift reader expectations during a sceneThe last few tips involved building suspense across many chapters. However, you should also aim to create suspense within chapters. The same rules apply: the reader needs to care about an outcome and you should delay the answer. However, within a single chapter, you don't have much time. You might only have five, maybe 10 pages. A tactic you can use to compensate for the compressed timeline is to rapidly shift reader expectations during it. For instance, let's say you're writing a scene where a woman is running through the woods, away from a man who wants to hurt her. If you simply describe her running for three pages, yes, your reader will likely feel suspense. However, that suspense would be stronger if you fed in a stream of events that shifted reader expectations as to whether or not the woman gets away. Here's how you could do that:

Suspense Tip 7 - Use a ticking clockAs you now know, with good suspense, you want to make your audience wait for answers. However, you'd benefit by doing the opposite for your characters - you want to give them tight timeframes. In writing, a ticking clock is a deadline a character has to accomplish an important task. These clocks are sometimes literal - in an action story, the hero may have just three hours to find and diffuse a bomb with an actual ticking clock on it. A physical clock doesn't need to be involved, though - you just need a time crunch, regardless of the source. For example, in a romance story, the lead character has been offered a job in a new city. She has until June 1 to accept the offer. From now until then, she needs to decide if she wants to take the job or stay in town and pursue a relationship with a man she's falling for. A ticking clock builds suspense because it makes a promise to the reader: by a certain point in time, either something good or bad will definitely happen for a character. The definitiveness of the outcome makes the reader care more about it. As the clock ticks down, the feeling of suspense grows. To elevate the suspense of a ticking clock, you can use dramatic irony to put a character in a dangerous situation he isn't even aware of. For instance, the audience knows a bomb, set to go off in 30 minutes, is inside a building. Unaware, the main character walks inside. Suspense Tip 8 - Leverage cliffhangersWith a cliffhanger, you raise a question the audience cares about in a chapter and then end the chapter before giving the reader the answer. Though closing on any type of unanswered question technically constitutes a cliffhanger, the more dramatic kinds involve leaving a character in a pressing predicament. The obvious example is someone literally hanging off a cliff. If the reader cares about a character, and that character somehow has found his way onto the edge of a cliff, and falling means serious injury or death, end the chapter there and the reader should be very eager to turn the page to see what happens. Don't be afraid to close a lot of your chapters with a cliffhanger. That being said, if you end many chapters in a life-or-death predicament, your story may feel a bit forced. Vary the stakes and the immediacy of the chapter-ending questions. Suspense Tip 9 - Leverage crosscuttingWith crosscutting, you'd write a chapter from the POV of character A, then write the next chapter from the POV of character B, who is currently not with character A. You're essentially jumping in space. At the end of a chapter, if the audience is left wondering how certain events will play out for character A, cutting to character B delays the reveal of information about character A, infusing suspense. After character B's chapter, if you again cut to character A (or even to C), the audience is left wondering about character B, ie even more suspense. The crosscutting technique works best in combination with pressing-predicament cliffhangers. The suspense around character A will be elevated when you cut to character B, if character A is left in physical danger or some other state of impending jeopardy. Suspense Tip 10 - Equip your antagonist for surpriseAs your protagonist pursues the want, the story's main villain should throw obstacles at the hero to prevent success. Make your villain a worthy opponent of your hero. Even better, make your villain more imposing than your hero, at least at the beginning of the book. A skilled, dynamic antagonist is capable of surprise. Thus, even when things seem to be going well for your protagonist, your audience will still feel suspense. If the reader knows a resilient villain, capable of crafty attacks, is lurking somewhere out there, the protagonist is never quite safe. A devastating surprise can come at any time. To learn more about antagonists, check out my post on writing great villains. What is suspense in storytelling?Suspense in storytelling is delaying the reveal of information the reader wants to know. The more the audience wants to know something, and the longer it waits, the greater the suspense. What types of stories need suspense?Though suspense is often associated with the action and thriller genres, it can be woven into stories of any genre. Yes, suspense is part of any quality gunfight or car-chase scene, but it's also what makes many subtler scenes work well. For example, in a domestic story, let's say a husband and wife are simply sitting at a table eating dinner. The reader knows the husband just told his wife a lie about where he was last night. When she asks him questions about the night, suspense is created. Will he will be exposed as a liar? Whatever type of story you're writing, it can benefit from an infusion of suspense. Best Free Creative Writing Course [Start Now]Learn how to turn your idea for a book or movie into a full-length novel or screenplay with the below video lessons of my free creative writing course. I'm also giving you a free outlining guide, which will help you apply the course lessons to your own story. What topics does my free creative course cover?My course is focused on fiction and narrative non-fiction. It doesn't address poetry, which varies quite a bit from the other two forms. However, if you're looking for a course on that subject, plenty exist. If your goal is to write a book or screenplay, the best free online writing class out there is the one I'm offering you. My course focuses on four major aspects of creative writing:

Not only do I provide in-depth video lessons, but a blueprint document you can follow to outline your story. My free creative writing class is for new writers, however, more experienced writers are likely to pick up some tips from it as well. Below, I go over the material the course addresses, plus provide clips of the video lessons for you to watch now. Topic #1 - Character developmentCharacter development is the technique of humanizing a fictional character. The more human a character feels, the more effective the character development. The process doesn't call for one type of humanity over any other. You may develop a character who's a righteous freedom fighter and another who's a serial killer. As long as they both feel human, you've done well as a writer. How to write a protagonistHow to write an antagonistTopic #2 - The plot of a storyThe plot of a story is the sequence of events its characters are involved in. The plot should build in a dramatic way toward the answer to this question: will the main character - ie, protagonist - achieve their central goal? This goal should be set fairly early in the story, after an event - known as the inciting incident - disturbs the hero's world and forces them to want something they lack. For instance, in a thriller story, the inciting incident could be a bank robbery that results in the death of a civilian. The crime causes the protagonist - an FBI agent - to want something: to catch the robber. The story would then follow the FBI agent as he pursued the antagonist criminal through a series of obstacles. It would build to a final showdown between the hero and villain, when the audience finally gets to know if the robber is caught or escapes. How to write a story plotTopic #3 - The theme of a storyThe theme of a story is the commentary about the world the story is making. For instance, in the story discussed above - about an FBI agent pursuing a murderous criminal - if the events end in justice, ie the criminal getting caught, the story would be making a different statement about society than if it ended in injustice, ie the criminal getting away. In the justice variation, the theme might be something like, "The world may be dark at times, but ultimately justice is served." In the injustice variation, the theme might be something like, "Despite the efforts of good people, some violent ones never pay for their crimes." How to write a story themeTopic #4 - Emotional impact in storytellingEmotional impact in storytelling is how frequently and strongly a story makes its audience feel emotion. As a writer, you need to create an emotional connection between your audience and characters with good characterization. If your characters feel like real humans, the humans in the audience will relate to them. Once you accomplish this, when your characters confront obstacles and go through ups and downs, your audience will have an emotional reaction, essentially going on the ride with them. This emotional ride is what a typical audience member is signing up for when they sit down to read a novel or watch a film. If you ask someone what their favorite book or movie is, the answer you get tends to be based on the person's emotional experience. For more on emotional impact in storytelling, watch this video clip from my writing course... The importance of emotional impact in storytellingFull free creative writing courseYou can watch the complete free creative course (over 30 minutes of video lessons) here: What genres is the free online writing course for?The course is aimed at fiction and narrative non-fiction writers. The lessons are applicable to all genres within those two categories, such as:

Download the accompanying outlining guideWhether you're a beginner looking to finish a first book or screenplay, or an experienced writer hoping to pick up a few new skills, be sure to download the story-outlining guide that accompanies the video lessons of the creative writing course. Additional writing coursesHere's a list of some other writing classes you may be interested in, too. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed